YOGI BERRA, YANKEE WHO BUILT HIS STARDOM 90 PERCENT ON SKILL AND HALF ON WIT

Yogi Berra, one of baseball’s greatest catchers and characters, who as a player was a mainstay of 10 Yankees championship teams and as a manager led both the Yankees and the Mets to the World Series — but who may be more widely known as an ungainly but lovable cultural figure, inspiring a cartoon character and issuing a seemingly limitless supply of unwittingly witty epigrams known as Yogi-isms — died on Tuesday. He was 90.

The Yankees and the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center in Little Falls, N.J., announced his death. Before moving to an assisted living facility in nearby West Caldwell, in 2012, Berra had lived for many years in neighboring Montclair.

In 1949, early in Berra’s Yankees career, his manager assessed him this way in an interview in The Sporting News: “Mr. Berra,” Casey Stengel said, “is a very strange fellow of very remarkable abilities.”

And so he was, and so he proved to be. Universally known simply as Yogi, probably the second most recognizable nickname in sports — even Yogi was not the Babe — Berra was not exactly an unlikely hero, but he was often portrayed as one: an All-Star for 15 consecutive seasons whose skills were routinely underestimated; a well-built, appealingly open-faced man whose physical appearance was often belittled; and a prolific winner, not to mention a successful leader, whose intellect was a target of humor if not outright derision.

That he triumphed on the diamond again and again in spite of his perceived shortcomings was certainly a source of his popularity. So was the delight with which his famous, if not always documentable, pronouncements — somehow both nonsensical and sagacious — were received.

“You can observe a lot just by watching,” he is reputed to have declared once, describing his strategy as a manager.

“If you can’t imitate him,” he advised a young player who was mimicking the batting stance of the great slugger Frank Robinson, “don’t copy him.”

“When you come to a fork in the road, take it,” he said, giving directions to his house. Either path, it turned out, got you there.

“Nobody goes there anymore,” he said of a popular restaurant. “It’s too crowded.”

Whether Berra actually uttered the many things attributed to him, or was the first to say them, or phrased them precisely the way they were reported, has long been a matter of speculation. Berra himself published a book in 1998 called “The Yogi Book: I Really Didn’t Say Everything I Said!” But the Yogi-isms testified to a character — goofy and philosophical, flighty and down to earth — that came to define the man.

Berra’s Yogi-ness was exploited in advertisements for myriad products, among them Puss ’n Boots cat food and Miller Lite beer but perhaps most famously Yoo-Hoo chocolate drink. Asked if Yoo-Hoo was hyphenated, he is said to have replied, “No, ma’am, it isn’t even carbonated.”

If not exactly a Yogi-ism, it was the kind of response that might have come from Berra’s ursine namesake, the affable animated character Yogi Bear, who made his debut in 1958.

An Impressive Résumé

The character Yogi Berra may even have overshadowed the Hall of Fame ballplayer Yogi Berra, obscuring what a remarkable athlete he was. A notorious bad-ball hitter — he swung at a lot of pitches that were not strikes but mashed them anyway — he was fearsome in the clutch and the most durable and consistently productive Yankee during the period of the team’s most relentless success.

In addition, as a catcher, he played the most grueling position on the field. (For a respite from the chores and challenges of crouching behind the plate, Berra, who played before the designated hitter rule took effect in the American League in 1973, occasionally played the outfield.)

Stengel, a Hall of Fame manager whose shrewdness and talent were also often underestimated, recognized Berra’s gifts. He referred to Berra, even as a young player, as his assistant manager and compared him favorably to star catchers of previous eras like Mickey Cochrane, Gabby Hartnett and Bill Dickey. “You could look it up” was Stengel’s catchphrase, and indeed the record book declares that Berra was among the greatest catchers in the history of the game — some say the greatest of all.

Berra’s career batting average, .285, was not as high as that of his Yankees predecessor, Dickey (.313), but Berra hit more home runs (358 in all) and drove in more runs (1,430). Praised by pitchers for his astute pitch-calling, Berra led the American League in assists five times and from 1957 through 1959 went 148 consecutive games behind the plate without making an error, a major league record at the time.

He was not a defensive wizard from the start, though. Dickey, Berra explained, “learned me all his experience.”

On defense, he certainly surpassed Mike Piazza, the best-hitting catcher of recent vintage, and maybe ever. On offense, Berra and Johnny Bench, whose Cincinnati Reds teams of the 1970s were known as the Big Red Machine, were comparable, except that Bench struck out three times as often. Berra whiffed a mere 414 times in more than 8,300 plate appearances over 19 seasons — an astonishingly small ratio for a power hitter.

Others — Carlton Fisk, Gary Carter and Ivan Rodriguez among them — also deserve consideration in a discussion of great catchers, but none was clearly superior to Berra on offense or defense. Only Roy Campanella, a contemporary rival who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers and faced Berra in the World Series six times before his career was ended by a car accident, equaled Berra’s total of three Most Valuable Player Awards. And although Berra did not win the award in 1950 — his teammate Phil Rizzuto did — he gave one of the greatest season-long performances by a catcher that year, hitting .322, smacking 28 home runs and driving in 124 runs.

Big Moments

Berra’s career was punctuated by storied episodes. In Game 3 of the 1947 World Series, against the Dodgers, he hit the first pinch-hit home run in Series history, and in Game 4 he was behind the plate for what was almost the first no-hitter and was instead a stunning loss. With two outs in the ninth inning and two men on base after walks, the Yankees’ starter, Bill Bevens, gave up a double to Cookie Lavagetto that cleared the bases and won the game.

In September 1951, once again on the brink of a no-hitter, this one by Allie Reynolds against the Boston Red Sox, Berra made one of baseball’s famous errors. With two outs in the ninth inning, Ted Williams hit a towering foul ball between home plate and the Yankees’ dugout. It looked like the end of the game, which would seal Reynolds’s second no-hitter of the season and make him the first American League pitcher to accomplish that feat. But as the ball plummeted, it was caught in a gust of wind; Berra lunged backward, and it deflected off his glove as he went sprawling.

Amazingly, on the next pitch, Williams hit an almost identical pop-up, and this time Berra caught it.

In the first game of the 1955 World Series against the Dodgers, the Yankees were ahead, 6-4, in the top of the eighth when the Dodgers’ Jackie Robinson stole home. The plate umpire, Bill Summers, called him safe, and Berra went berserk, gesticulating in Summers’s face and creating one of the enduring images of an on-the-field tantrum. The Yankees won the game although not the Series — it was the only time Brooklyn got the better of Berra’s Yankees — but Berra never forgot the moment. More than 50 years later, he signed a photograph of the play for President Obama, writing, “Dear Mr. President, He was out!”

During the 1956 Series, again against the Dodgers, Berra was at the center of another indelible image, this one of sheer joy, when he leapt into the arms of Don Larsen, who had just struck out Dale Mitchell to end Game 5 and complete the only perfect game (and only no-hitter) in World Series history.

When reporters gathered at Berra’s locker after the game, he greeted them mischievously. “So,” he said, “what’s new?”

Beyond the historic moments and individual accomplishments, what most distinguished Berra’s career was how often he won. From 1946 to 1985, as a player, coach and manager, Berra appeared in a remarkable 21 World Series. Playing on powerful Yankees teams with teammates like Rizzuto and Joe DiMaggio early on and then Whitey Ford and Mickey Mantle, Berra starred on World Series winners in 1947, ’49, ’50, ’51, ’52, ’53, ’56 and ’58. He was a backup catcher and part-time outfielder on the championship teams of 1961 and ’62. (He also played on World Series losers in 1955, ’57, ’60 and ’63.)

All told, his Yankees teams won the American League pennant 14 out of 17 years. He still holds Series records for games played, plate appearances, hits and doubles.

No other player has been a champion so often.

Lawrence Peter Berra was born on May 12, 1925, in the Italian enclave of St. Louis known as the Hill, which also fostered the baseball career of his boyhood friend Joe Garagiola. Berra was the fourth of five children. His father, Pietro, a construction worker and bricklayer, and his mother, Paulina, were immigrants from Malvaglio, a northern Italian village near Milan. (As an adult, on a visit to his ancestral home, Berra took in a performance of “Tosca” at La Scala. “It was pretty good,” he said. “Even the music was nice.”)

As a boy, Berra was known as Larry, or Lawdie, as his mother pronounced it. As recounted in “Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee,” a 2009 biography by Allen Barra, one day in his early teens, young Larry and some friends went to the movies and were watching a travelogue about India when a Hindu yogi appeared on the screen sitting cross-legged. His posture struck one of the friends as precisely the way Berra sat on the ground as he waited his turn at bat. From that day on, he was Yogi Berra.

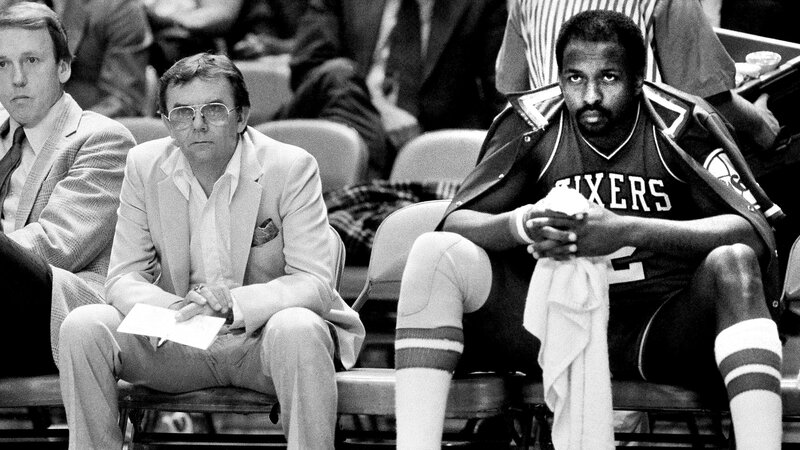

George Steinbrenner, right, with Yogi Berra in 1985 before Steinbrenner made “the worst mistake I ever made in baseball,” firing Berra as manager. Credit United Press International

An ardent athlete but an indifferent student, Berra dropped out of school after the eighth grade. He played American Legion ball and worked odd jobs. As teenagers, he and Garagiola tried out with the St. Louis Cardinals and were offered contracts by the Cardinals’ general manager, Branch Rickey. But Garagiola’s came with a $500 signing bonus and Berra’s just $250, so Berra declined to sign. (This was a harbinger of deals to come. Berra, whose salary as a player reached $65,000 in 1961, substantial for that era, proved to be a canny contract negotiator, almost always extracting concessions from the Yankees’ penurious general manager, George Weiss.)

In the meantime, the St. Louis Browns — they later moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles — also wanted to sign Berra but were not willing to pay any bonus at all. Then, the day after the 1942 World Series, in which the Cardinals beat the Yankees, a Yankees coach showed up at Berra’s parents’ house and offered him a minor league contract — along with the elusive $500.

A Fan Favorite

Berra’s professional baseball life began in Virginia in 1943 with the Norfolk Tars of the Class B Piedmont League. In 111 games he hit .253 and led the league’s catchers in errors, but he reportedly once had 12 hits and drove in 23 runs over two consecutive games. It was a promising start, but World War II put his career on hold. Berra joined the Navy. He took part in the invasion of Normandy and, two months later, in Operation Dragoon, an Allied assault on Marseilles in which he was bloodied by a bullet and earned a Purple Heart.

In 1946, after his discharge, he was assigned to the Newark Bears, then the Yankees’ top farm team. He played outfield and catcher and hit .314 with 15 home runs and 59 R.B.I. in 77 games, although his fielding still lacked polish; in one instance he hit an umpire with a throw from behind the plate meant for second base. But the Yankees still summoned him in September. In his first big league game, he had two hits, including a home run.

As a Yankee, Berra became a fan favorite, partly because of his superior play — he batted .305 and drove in 98 runs in 1948, his second full season — and partly because of his humility and guilelessness. In 1947, honored at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, a nervous Berra told the hometown crowd, “I want to thank everyone for making this night necessary.”

Berra was a hit with sportswriters, too, although they often portrayed him as a baseball idiot savant, an apelike, barely literate devotee of comic books and movies who spoke fractured English. So was born the Yogi caricature, of the triumphant rube.

“Even today,” Life magazine wrote in July 1949, “he has only pity for people who clutter their brains with such unnecessary and frivolous matters as literature and the sciences, not to mention grammar and orthography.”

Collier’s magazine declared, “With a body that only an anthropologist could love, the 185-pound Berra could pass easily as a member of the Neanderthal A.C.”

Berra tended to take the gibes in stride. If he was ugly, he was said to have remarked, it did not matter at the plate. “I never saw nobody hit one with his face,” he was quoted as saying. But when writers chided him about his girlfriend, Carmen Short, saying he was too unattractive to marry her, he responded, according to Colliers, “I’m human, ain’t I?”

Berra outlasted the ridicule. He married Short in 1949, and the marriage endured until her death in 2014. He is survived by their three sons — Tim, who played professional football for the Baltimore Colts; Dale, a former infielder for the Yankees, the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Houston Astros; and Lawrence Jr. — as well as 11 grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Certainly, assessments of Berra changed over the years.

“He has continued to allow people to regard him as an amiable clown because it brings him quick acceptance, despite ample proof, on field and off, that he is intelligent, shrewd and opportunistic,” Robert Lipsyte wrote in The New York Times in October 1963.

Success as a Manager

At the time, Berra had just concluded his career as a Yankees player, and the team had named him manager, a role in which he continued to find success, although not with the same regularity he enjoyed as a player and not without drama and disappointment. Indeed, things began badly. The Yankees, an aging team in 1964, played listless ball through much of the summer, and in mid-August they lost four straight games in Chicago to the first-place White Sox, leading to one of the kookier episodes of Berra’s career.

On the team bus to O’Hare Airport, the reserve infielder Phil Linz began playing “Mary Had a Little Lamb” on the harmonica. Berra, in a foul mood over the losing streak, told him to knock it off, but Linz did not. (In another version of the story, Linz asked Mickey Mantle what Berra had said, and Mantle responded, “He said, ‘Play it louder.’ ”) Suddenly the harmonica went flying, having been either knocked out of Linz’s hands by Berra or thrown at Berra by Linz. (Players on the bus had different recollections.)

News reports of the incident made it sound as if Berra had lost control of the team, and although the Yankees caught and passed the White Sox in September, winning the pennant, Ralph Houk, the general manager, fired Berra after the team lost a seven-game World Series to St. Louis. In a bizarre move, Houk replaced him with the Cardinals’ manager, Johnny Keane.

Keane’s Yankees finished sixth in 1965.

Berra, meanwhile, moved across town, taking a job as a coach for the famously awful Mets under Stengel, who was finishing his career in Flushing. The team continued its mythic floundering until 1969, when the so-called Miracle Mets, with Gil Hodges as manager — and Berra coaching first base — won the World Series.

After Hodges died, before the start of the 1972 season, Berra replaced him. That summer, Berra was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

The Mets team he inherited, however, faltered, finishing third, and for most of the 1973 season they were worse. In mid-August, the Mets were well under .500 and in sixth place when Berra supposedly uttered perhaps the most famous Yogi-ism of all.

“It ain’t over till it’s over,” he said (or words to that effect), and lo and behold, the Mets got hot, squeaking by the Cardinals to win the National League’s Eastern Division title.

They then beat the Reds in the League Championship Series before losing to the Oakland Athletics in the World Series. Berra was rewarded for the resurgence with a three-year contract, but the Mets were dreadful in 1974, finishing fifth, and the next year, on Aug. 6, with the team in third place and having lost five straight games, Berra was fired.

Once again he switched leagues and city boroughs, returning to the Bronx as a Yankees coach, and in 1984 the owner, George Steinbrenner, named him to replace the volatile Billy Martin as manager. The team finished third that year, but during spring training in 1985, Steinbrenner promised him that he would finish the season as Yankees manager no matter what.

After just 16 games, however, the Yankees were 6-10, and the impatient and imperious Steinbrenner fired Berra anyway, bringing back Martin. Perhaps worse than breaking his word, Steinbrenner sent an underling to deliver the bad news.

The firing, which had an added sting because Berra’s son Dale had recently joined the Yankees, provoked one of baseball’s legendary feuds, and for 14 years Berra refused to set foot in Yankee Stadium, a period during which he coached four seasons for the Houston Astros.

In the meantime private donors helped establish the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center on the New Jersey campus of Montclair State University, which awarded Berra an honorary doctorate of humanities in 1996. A minor league ballpark, Yogi Berra Stadium, opened there in 1998.

The museum, a tribute to Berra with exhibits on his career, runs programs for children dealing with baseball history. In January 1999, Steinbrenner, who died in 2010, went there to make amends.

“I know I made a mistake by not letting you go personally,” he told Berra. “It’s the worst mistake I ever made in baseball.”

Berra chose not to quibble with the semi-apology. To welcome him back into the Yankees fold, the team held a Yogi Berra Day on July 18, 1999. Also invited was Larsen, who threw out the ceremonial first pitch, which Berra caught.

Incredibly, in the game that day, David Cone of the Yankees pitched a perfect game.

It was, as Berra may or may not have said in another context, “déjà vu all over again,” a fittingly climactic episode for a wondrous baseball life.

Correction: September 23, 2015

An earlier version of this obituary referred incorrectly to the Yankees’ finish in 1965, the year Johnny Keane replaced Berra as manager. The team finished sixth (in what was then a 10-team league), not last. The Yankees finished last in 1966.

Correction: September 23, 2015

An earlier version of this obituary contained an incomplete list of survivors. In addition to his three sons, Berra is survived by 11 grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Correction: September 25, 2015

A picture on Thursday with the continuation of an obituary about Yogi Berra, the Hall of Fame Yankees catcher, was published in error. It showed Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers being called out at home after a tag by New York Giants catcher Ray Katt on a failed squeeze bunt attempt by Clem Labine on May 13, 1956. It did not show Robinson’s famous steal of home against Berra and the Yankees in Game 1 of the 1955 World Series.

SOURCE

********************************************

BEN CAULEY, SOLE SURVIVOR OF OTIS REDDING PLANE CRASH

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESSSEPT. 24, 2015

Ben Cauley, who played trumpet with the rhythm-and-blues group the Bar-Kays and was the only survivor of the 1967 plane crash that killed Otis Redding, died on Monday in Memphis. He was 67.

Ben Cauley in 2007. He survived the 1967 plane crash that killed Otis Redding. Credit Mike Maple/The Commercial Appeal, via Associated Press

His death was confirmed by his eldest daughter, Chekita Cauley-Campbell. It was first reported by the Memphis newspaper The Commercial Appeal.

Mr. Cauley started playing with the Bar-Kays while attending Booker T. Washington High School in Memphis, his daughter said. The group recorded for the Stax label and soon started touring as Redding’s backup band. They would be picked up on a Friday, travel and play with Redding on the weekend and return to school for the week.

On Dec. 10, 1967, Mr. Cauley and most of the other members of the band were traveling on Redding’s new twin-engine Beechcraft when it crashed into Lake Monona, near Madison, Wis. Able to hold onto a seat cushion, Mr. Cauley was the only survivor. Another band member, the bassist James Alexander, was on a different plane.

After the crash, Mr. Cauley and Mr. Alexander rebuilt the Bar-Kays. The new version of the band backed Isaac Hayes on his landmark 1969 album, “Hot Buttered Soul,” and recorded several albums of its own.

Mr. Cauley had various health problems in recent years, including a stroke he suffered in 1989, but he continued to perform.

In addition to Ms. Cauley-Campbell, he is survived by four other daughters, Shuronda Cauley-Oliver, Miriam Cauley-Crisp, Monica Cauley-Johnson and Kimberly Garrett, and two sons, Phalon Richmond and Ben Wells.

SOURCE

**********************************************

ELIZABETH M. FINK, A LAWYER WHO REPRESENTED RADICALS AND INMATES

NEW YORK — Elizabeth M. Fink, a fiery advocate for society’s outcasts who devoted much of her law career to vindicating and compensating inmate victims of the 1971 Attica prison uprising, died Tuesday in New York. She was 70.

Ms. Fink with reporters in 1999. She defended Black Panthers, inmates, and conspirators. HENNY RAY ABRAMS/AFP/Getty Images/FileMs

By Sam Roberts New York Times September 26, 2015

Her brother, photographer Larry Fink, said the cause was cardiac arrest.

Born into leftist politics as a self-described “red diaper baby,” Ms. Fink represented a panoply of pariahs during four decades.

They included Cathy Wilkerson, who was accused in a Weather Underground bomb-making conspiracy; members of the Puerto Rican nationalist group FALN; a Black Panther Party leader who was charged with attempted murder in a machine-gun attack on two New York police officers; Lynne F. Stewart, a fellow radical lawyer; and an Algerian immigrant who pleaded guilty in a plot to bomb a Manhattan synagogue.

Ms. Fink was just one month out of law school in 1974 when she helped draft a $2.8 billion civil suit on behalf of inmates who were killed and brutalized during and after the bloody revolt at the Attica Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in western New York. The riot was incited by overcrowding and other abuses.

When a five-day siege by state troopers ended, 10 correctional officers and civilian employees and 33 prisoners were dead. All but one guard and three inmates were killed in what a prosecutor branded a State Police “turkey shoot.”

In 2000, Ms. Fink, as lead counsel in the federal civil rights case, won an $8 million settlement from the state, plus $4 million in legal fees.

She waged her fights both in the courts and in the court of public opinion. But unlike Stewart, who was convicted of supporting terrorists by passing messages from an imprisoned client, an Egyptian cleric, Ms. Fink never pivoted from conventional advocacy to illegal acts — although she had been tempted in the 1970s, she admitted.

“We were lawyers, but we were revolutionaries in our hearts,” she was quoted as saying in Bryan Burrough’s book “Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence,” which was published this year.

Many of the era’s radicals, she said, sought racial justice, inspired by the revolutionary oratory of the Black Panthers, who advocated self-defense and, if needed, violence.

“The civil rights movement had turned bad, and these people were ready to fight,” Ms. Fink was quoted in Burrough’s book. “And yeah, the war. The country was turning into Nazi Germany, that’s how we saw it.

“Do you have the guts to stand up? The underground did. And oh, the glamour of it. The glamour of dealing with the underground. They were my heroes. Stupid me. It was the revolution, baby. We were gonna make a revolution. We were so, so, so deluded.”

Elizabeth Marsha Fink (she was named for Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a founder of the American Civil Liberties Union and later national chairwoman of the Communist Party USA) was born in Brooklyn.

Her father, Bernard, was a lawyer. Her mother, the former Sylvia Caplan, was a nuclear weapons protester and later, at the UN, a representative of the Gray Panthers, an elder-rights group that cast itself there as a nongovernmental organization.

Ms. Fink graduated from Reed College in Oregon in 1967 and from Brooklyn Law School.

An acolyte of the defense lawyer William M. Kunstler (she later mentored his daughter Sarah, also a lawyer), Ms. Fink typically represented criminals and radicals pro bono from her Brooklyn office while more respected clients paid the freight. One was O. Aldon James Jr., the former president of the prestigious National Arts Club, who was ousted over allegations of misuse of club money and property.

In 1990, Ms. Fink did a sprightly dance at the defense table, then wept, when she won the release of Dhoruba al-Mujahid bin Wahad, a former Black Panther who had served nearly 19 years in prison for the 1971 attempted murder of two police officers assigned to guard the home of the Manhattan district attorney, Frank S. Hogan.

The conviction was reversed after she and her co-counsel, Robert Boyle, in a civil suit, produced evidence that had been withheld by the authorities at earlier trials.

The Attica lawsuit pursued by Ms. Fink and other lawyers, including her co-counsel, Michael Deutsch, against an unrepentant state was chronicled in “Ghosts of Attica,” a Court TV documentary broadcast in 2001.

Her tenacity in the Attica case even won plaudits from Dee Quinn Miller, whose father, William Quinn, was the only guard killed by inmates during the uprising.

“We both were after the truth,” Miller said in a phone interview on Thursday.

In 1997, the lawyers won $4 million for one of the inmates, Frank B.B. Smith, a high school dropout who by then had become a paralegal in Ms. Fink’s office. His award was later reduced to $125,000; others went as low as $6,500.

In 2006, Ms. Fink helped free a Jordanian immigrant, Osama Awadallah, who had been accused of perjury when he denied knowing one of the Sept. 11 hijackers.

SOURCE