LEO BRETHOLZ; ESCAPED NAZI TRAIN TO AUSCHWITZ

Mr. Bretholz, who died at 93 on March 8, would describe how, as a Jew, he had evaded Nazi concentration camps by living as a fugitive from 1938 to 1945, hunted in almost every country in Europe by the Nazis and their collaborators in Belgium, France, Luxembourg and Austria.

The Nazis had many helpers in capturing those they would tattoo, he explained.

The high point of his talk was the account of his leap from the train carrying him and a thousand other Jewish deportees to Auschwitz on Nov. 5, 1942. It was a French train, he said, operated by the state-owned railway, the Société Nationale des Chemins de fer Français, or S.N.C.F.

His escape, he said, came after he and another man had studied the railway guards’ surveillance routines. Prying loose the bars of a small window, they timed their jump from Convoy 42 on a curved stretch of rail somewhere in eastern France. Once the train slowed, they had “to avoid the floodlights, which the guards aimed over the entire length of the concave curvature of the train” at such junctures, he wrote in his 1998 memoir, “Leap Into Darkness: Seven Years on the Run in Wartime Europe.”

Mr. Bretholz, who lived in Pikesville, Md., repeated that account to students in the Baltimore area for years. Then, in 2000, it became eyewitness evidence in a class-action lawsuit seeking reparations from S.N.C.F.

The lawsuit died in 2011, after the United States Supreme Court declined to review a lower court’s ruling that the case was outside American jurisdiction. But when S.N.C.F. became involved in commuter rail contracts in Maryland, Mr. Bretholz became a prominent voice in the reparations effort.

“All I want is a declaration — a forceful declaration — of: ‘We did something very wrong, something inhumane. We sent people to their deaths,’ ” Mr. Bretholz told The Washington Post in an interview this year.

He became the star witness at congressional hearings on the proposed Holocaust Rail Justice Act, which would allow Holocaust victims and their families to sue S.N.C.F. in the American courts. He testified a half dozen times before panels of the Maryland State Legislature to support legislation that would bar S.N.C.F. from bidding on a planned $6 billion high-speed rail system unless it acknowledged its role and agreed to compensate victims. He had been scheduled to testify again in Annapolis on the Monday after his death.

S.N.C.F. has long acknowledged that it transported 76,000 Jews and other so-called “undesirables” to Auschwitz from the Drancy internment camp outside Paris. But it has refused to pay reparations, saying it had acted under duress, by orders of France’s German occupiers.

By Mr. Bretholz’s account, however, S.N.C.F. was actively complicit in the horrors of the deportations. The rail operators packed people into cattle cars, he said, leaving barely room to sit. They failed to provide adequate food or water. They were vigilant in keeping their passengers from escaping.

Wartime France, he wrote, was “the most important and very venal cog in the wheel of Hitler’s Holocaust co-conspirators.”

He left Vienna at 17 with a train ticket purchased by his mother, amid the growing menace of Nazi control, arriving in Trier, at the western edge of Germany. He then forded the Sauer River into Luxembourg and found his way to Belgium.

Mr. Bretholz traveled on a kind of Underground Railroad for the stateless Jews of Europe for the next seven years. He found sanctuary with relatives, in Jewish ghettos, among orders of Roman Catholic nuns and priests. He assumed aliases and slept in ditches. Toward the end of the war, he joined a Jewish resistance group known as La Sixièeme. After the war he settled in Baltimore, where he had relatives. He found work in the textile business, then as a partner in a liquor store, then in the book selling business.

In 1962, he received a letter from the Jewish Community Council of Vienna. It spoke of his mother and two sisters, who had been sent to a Nazi transit ghetto in occupied Poland:

“This is to confirm that, according to our records, Mrs. Dora Bretholz, Miss Henriette Bretholz and Miss Edith Bretholz were deported to Izbica on 9 April 1942 and that they do not appear on the list of returnees.”

Mr. Bretholz’s daughter Edie Norton, who confirmed her father’s death, at his home, quoted the letter in an email Wednesday. She said his receiving the bureaucratic notification decades after he last saw his family made her father determined to tell his family’s story. Besides her, Mr. Bretholz is survived by another daughter, Denise Harris; a son, Myron; a half-sister, Helen Meyer; and four grandchildren. His wife of 57 years, Florence Cohen Bretholz, died in 2009.

At one of his last talks in a classroom several years ago, filmed for a short documentary, “See You Soon Again,” Mr. Bretholz said that in his considered view there was no real distinction between Holocaust “survivors” and everybody else.

“If that evil had conquered the world,” he said, “we wouldn’t be here. You are all survivors.”

*******************************************************

VERA CHYTILOVA; MADE DARING FILMS IN CZECH NEW WAVE

Ms. Chytilova died after a long illness, her family told the Czech national news agency, CTK.

The only prominent woman among the Czech New Wave directors —a group of avant-garde auteurs in the 1960s who included Milos Forman and Jiri Menzel — Ms. Chytilova was known for films that were formally rigorous even by the standards of the movement.

Mordant, darkly farcical satires of life in Communist Czechoslovakia, Ms. Chytilova’s movies might employ disjointed, nonlinear narratives; rapid, deliberately dizzying cuts; speeded-up or slowed-down action; and stark shifts between black-and-white and color from one scene to the next.

In a 1978 profile, The New York Times described her as “a director long considered in the first rank of Czechoslovak filmmakers, who once were numbered among the best in the world.”

Ms. Chytilova’s best-known film, “Daisies,” completed in 1966 but banned in Czechoslovakia until the next year, is widely regarded as her masterwork.

That film, hedonist and picaresque, follows two young disaffected Czech women, Marie I and Marie II, through a series of pranks as they flaunt their nubile sexuality, toy with the affections of a string of hapless men and engage in the gleeful, wanton destruction of property.

In a retrospective article about “Daisies” in 2012, The Boston Globe said it embodied “the ethos of the Prague Spring turbocharged.”

In the film’s most emblematic moment, in which female erotic power is reimagined as an orgy of gastronomic sabotage, the Maries ravish a banquet by literally walking over it, their stiletto heels spearing all manner of delicacies as they shimmy down the table.

The scene caused the picture to be denounced on the floor of the Czech Parliament for the amount of food — “the fruit of the work of our toiling farmers” — expended in the making of it.

“Daisies,” which was shown in several Western cities soon after its completion, won the grand prize at the Bergamo Film Festival in Italy. Over the years, Ms. Chytilova’s work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Brooklyn Academy of Music and the New York Film Festival.

Her next film, “(We Eat) the Fruits of Paradise,” a dark spin on the Adam and Eve story involving a suspected serial killer, was released in 1970. But with the liberalization of the Prague Spring uprising of 1968 overturned by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia that year, she was barred from making films for nearly a decade.

Vera Chytilova was born on Feb. 2, 1929, in Ostrava, now in the Czech Republic. After university studies in philosophy and architecture, she held a series of jobs: technical draftsman, photo retoucher, fashion model and, finally, “clapper girl” at the Czech national film studio.

Enthralled by the filmmaking process, she rose to become an assistant director there. She later trained at the film school of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague.

Unlike many prominent Czech filmmakers — Mr. Forman, for instance, who settled in the United States and whose films include “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and “Amadeus” — Ms. Chytilova chose to remain in Czechoslovakia after 1968.

For one thing, she saw herself as more provocateur than dissident: though disenchanted with its specific manifestations, she retained an essential belief in the socialist cause.

In the mid-1970s, frustrated by her inability to ply her craft — she was then directing TV commercials under a pseudonym — Ms. Chytilova wrote to the Czech president, Gustav Husak, restating her belief in socialism and saying, “I want to work!”

The ban was lifted, though her films remained subject to the same level of government censorship as the work of other Czech artists.

Ms. Chytilova’s next film, “The Apple Game,” the story of sexual escapades in a hospital maternity ward, was completed in 1977. When it opened the next year at a single theater in Prague, The Times reported, “lines formed around the block.”

Her later films include “The Very Late Afternoon of a Faun,” about an aging Lothario; “Tainted Horseplay,” about AIDS; and “Expulsion From Paradise,” about nudists.

If Ms. Chytilova’s work after the fall of Czech Communism in 1989 lacked the bite — and the critical reception — of her earlier pictures, she did not want for subject matter. In one of her best-known post-Communist films, “The Inheritance,” she lampooned the new capitalist fervor sweeping the former East bloc.

Ms. Chytilova’s husband, Jaroslav Kucera, a noted Czech cinematographer who shot many of her films, died in 1991. Survivors include a son, Stepan Kucera, and a daughter, Tereza Kucerova.

As she made clear in a 2004 Czech documentary, “Journey: Portrait of Vera Chytilova,” Ms. Chytilova had no regrets about the manner in which she approached her career.

“I was daring enough to want to do what I wanted,” she said, “even if it was a mistake.”

*******************************************************

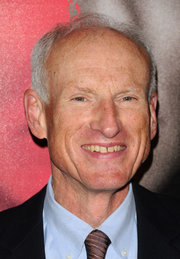

JAMES REBHORN, AN ACTOR OFTEN PLAYING A MAN IN A SUIT

The cause was melanoma, his agent, Dianne Busch, said.

Mr. Rebhorn had memorable supporting roles in major films and worked consistently in television and theater. He appeared in more than 50 films, including “Meet the Parents,” “Independence Day,” “My Cousin Vinny” and “Cold Mountain.”

In the acclaimed political thriller “Homeland,” now in its fourth season on Showtime, he played the pivotal role of Frank Mathison, the father of Carrie Mathison, the C.I.A. officer played by Claire Danes. The show has chronicled how both father and daughter have grappled with bipolar disorder.

Tall and lanky with an ever-receding hairline, Mr. Rebhorn liked to joke that his characters tended to wear suits, whether he was the secretary of defense in “Independence Day,” the 1996 blockbuster about an alien invasion, or an assistant district attorney in the ballyhooed series finale of “Seinfeld.”

On stage, Mr. Rebhorn was active in the Roundabout Theater Company and appeared on Broadway in a successful 2004-05 revival of “Twelve Angry Men,” playing a juror; in the short-lived “Prelude to a Kiss” in 2007; in Arthur Miller’s “The Man Who Had All the Luck” in 2002; and a production of Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town” in 1988-89, among other plays.

Last year he played a character with Alzheimer’s disease in Meghan Kennedy’s “Too Much, Too Much, Too Many,” at the Roundabout Underground’s Black Box Theater.

“Although his role is perhaps the play’s smallest, Mr. Rebhorn gives a beautiful portrait of a man struggling to come to terms with his faltering mind,” the critic Charles Isherwood wrote in The New York Times.

James Rebhorn was born on Sept. 1, 1948, in Philadelphia. He said he had considered becoming a Lutheran minister but ultimately decided to study political science and theater at Wittenberg University in Ohio. He then moved to New York and received a master’s degree in fine arts from Columbia University.

Mr. Rebhorn began working in theater and television commercials as well as on soap operas before he started appearing in films. In the 1980s he acted in a number of television movies and the theatrical release “Silkwood.” In the 1990s he had supporting roles in films like “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” “Scent of a Woman,” “Basic Instinct,” “Carlito’s Way,” “Lorenzo’s Oil” and Woody Allen’s “Shadows and Fog.” More recently he appeared in “The Odd Life of Timothy Green” and “Sleepwalk With Me,” both in 2012. He continued to work in television as well, appearing in “Law & Order” and “The Practice,” and he had recurring roles on USA’s “White Collar” and on HBO’s “Enlightened.”

He is survived by his wife, Rebecca Linn, and his daughters, Hannah and Emma.

In an interview in 2007, Mr. Rebhorn said that he had tried to do one play every year because he enjoyed the immediate feedback from the audience. He allowed that it could be difficult to escape the roles people were used to seeing him in — the lawyers and politicians — but he noted that he had recently played a farmer in a Hallmark Hall of Fame special called “Candles on Bay Street.”

“It was a small role, but it was a pleasure to be a character who doesn’t wear a suit,” he said.

Weather stations help pass information about weather forecasts and temperatures.

Weather stations help pass information about weather forecasts and temperatures.