The following essay is an excerpt from a response I gave to a commentor on the site backintyme.com concerning the savage sexual abuse that black women endured during Reconstruction and Jim Crow segregation. My original comment was posted on August 16, 2006. Some additional comment has been added to my original post. In the following essay, I further state how the sexualized gendered racism directed against black women and girls further drove the nails into the coffin of the devaluation of black women, a devaluation that exists still in the 21ST Century:

Much that has been written about slavery and how it has physically affected black women, while not discussing the psychological effects. But, there are two other aspects of black women’s lives in this country that are rarely if ever discussed concerning the physical cruelties they suffered at the hands of white men: the degradation of black women by white men during Reconstruction and during Jim Crow segregation. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction was the height of the Southern whites attempts to beat and force black people back into slavery. The reign of terror known as Jim Crow segregation continued the vicious sexual assaults upon black women and girls bodies and minds.

After slavery ended, white men lost their legal de jure control over black women’s bodies. With the institution of Jim Crow segregation with Plessy vs. Ferguson, and the enactment of the “separate, but unequal” doctrine, a new era of slavery was ushered in. I prefer to call it “Segregation–Slavery, the Sequel.” White men and women refused to let black people, those with property and those who were poor, live lives of peace. The reign of terror was instituted by Jim Crow laws, and during Reconstruction, the Ku Klux Klan was the chief embodiment of this vicious hatred towards black people. Blacks were only too happy to get away from white people, but white people were determined to push black people back into slavery. And the Klan did its part in the bestial acts of depravity it committed against black people, without any intervention of the law. And with the strengthening of legalized de jure Jim Crow laws and de facto social racial violence, whites subjugated black people into a peonage slavery known as share-cropping, as well as the forcing of black women into domestic labor, the only work they were allowed and had to do to keep the black family from starving, as the white race refused black men employment.

The Klan manifested its determination to reassert white racial domination with particular clarity in its abiding hostility to the notion of “social equality,” which, in addition to its literal meanings, was an oft-deployed euphermism for interracial sex. And this was most pernicious in the sexualized gendered racism against black people.

“A pointed exchange between Z. B. Hargrove, an attorney and former Confederate officer, and his congressional examiner suggests some of the ways in which the white South’s distorted conception of a growing black menace was inflected by prevailing notions of race, gender and class:

“Q: Do the negroes assert social equality with the whites?

“A: No, not in the least. In my section of the State they are very humble and very obedient….

“Q: Do they make any attempt to intermarry and mix with the whites?

“A: I believe in one or two instances white women have married colored men; that is all a question of taste.

“Q: Is it a rule, or do they, as a rule, confine themselves to their own color?

“A: Yes, some poor, outcast, abandoned woman (white woman) will sometimes marry a colored man for the aid and assistance that he can give her, but there are very rare occurrences.

“Q: Is there any ground to fear miscegenation with the colored race?

“A: No, sir; it is all on the other foot.

“Q: What do you mean by the other foot?

“A: I mean that colored women have a great deal more to fear from white men.” (1)

As the testimony suggests, black men were not running white women down and raping them. It was the white man who was the initiator of sexual aggression against black women, and the white men were not averse to employing intimidation or worse to regain sexual access to black women. Popular racist myths aside, klansmen and their sympathizers found themselves hard pressed to document the supposedly out-of-control, ubiquitous black-on-white assaults. This tension between myth and reality is amplified by the following dialogue in which a klan sympathizer is questioned about the prevalence of rape in Mecklenburgh County, North Carolina:

“Q: Have there been many rapes by colored men on white women in your county?

“A: I do not recollect…Mecklenburgh has always been famous for rapes.

“Q: Do you recollect any rape committed upon a white woman by a colored man?

“A” I think there has been.

“Q: Can you name a case at all?

“Q: No, sir, I cannot; but I am pretty sure there has been more than one.” (1)

This witness knew of only one case of black-on-white rape in the Mecklenburgh County. But even this evidence was not enough to stop white racists from propagating the propaganda myth/lie that all black men rape, and that all white women were not safe around black men. But the manipulation of white supremacists of white’s anxieties of massive numbers of black men running amok and raping white women proved critical to the creation of the black man as “savage, rapist beast.” This influence is seen in the words of a John W. Gordon, who, when asked if there had been many black-on-white rapes in Georgia, earnestly replied:

“O, no sir; but one case of rape by a negro upon a white woman was enough to alarm the whole people of the State.” (1)

But the same could not be said for the helpless black women all across the South. The Klan’s propensity for using rape as an instrument of terror is a matter of public record. Witnesses who gave testimony at a number of Reconstruction-era tribunals often confronted the issue directly. Essic Harris, a North Carolina freedman, had this to say on the subject:

“Q: I understand you to say that a colored woman was ravaged by the Ku Klux Klan?

“A: Yes, sir.

“Q: Did you hear of any other case of that sort?

“A: Oh, yes, several times.That has been very common. The case I spoke of was close by me, and that is the reason I spoke of it. It has got to be an old saying.

“Q: You say it was common for the Ku Klux Klan to do that?

“A: Yes, sir. They say that if the women tell anything about it, they will kill them.” (1)

In addition to committing forced intercourse against black women, klansmen committed equally sick acts upon them. In one case of obvious symbolical oral rape, one klansman responded to the terrified cries of a freedwoman whose husband was in mortal danger, by thrusting a firebrand down her throat. Thomas White, a North Carolinian, came forward with testimony to a congressional committee investigating atrocities against freedmen and women with this testimony on a victim of another type of sexual attack, this time on a freedwoman named Violet Wallace:

“After having lashed, kicked and pummeled her about the head with a pistol, ‘one of the number stripped his pants down and sat down upon her face.’ While perpetrating these abuses, the nightriders mocked, ” ‘You think you are white, you think you are rich, you curse white folks.’ ” (1)

Like countless other victims, Wallace refused to either file a complaint or to speak publicly of the attack, fearing, as White put it, that the klansmen would “repeat the deed or take her life.” (1)

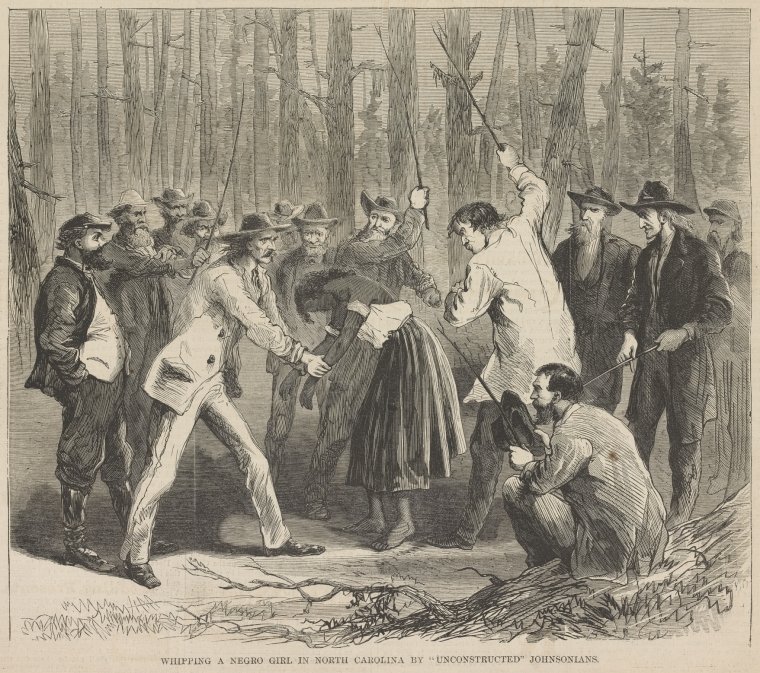

Image ID: 1692861

Whipping A Negro Girl In North Carolina By “Unconstructed” Johnsonians.

Other klan atrocities against black women, children and men were of the most horrible abuses:

“At the same time, there are many more explicit examples of the klan’s propensity for sexualized whipping. Although these assaults vary considerably in their particulars, with rare exception they reveal klansmen actively inducing their victims’s humiliation. This propensity was readily evidenced when, in the midst of a nighttime offensive, the KKK came upon the daughter of a freedman who had somehow provoked their ire and promptly set about to punish her in her father’s stead. Not satisfied with the tangible effects of the lashing they imposed, the klansmen continued to make her dance for their amusement. Hannah Travis, an ex-slave familiar with the ways of the Klan, describes an almost identical episode in which the nightriders pulled a pregnant woman from her bed and demanded that she dance while her husband helplessly looked on. Some attacks were more overtly still.Thomas Settle provided testimony regarding an episode in which klansmen “took a young negro who was in the house and whipped him, and compelled him to go through the form of sexual intercourse with one of the girls, whipping him at the same time,” all of this in the presence of the girl’s father. (1)

“Smith later recounts an exchange that ensued between two klansmen immediately prior to his wife’s chastisement that is striking in its savagery: ” ‘Don’t you want to use this hickory?’ or something like that. He (the klansman) said, “Yes, I want to taste of her meat.’ It would be difficult to conceive of a more explicit affirmation of the sexualized nature of such attacks as this one. By their words and deeds, the perpetrators expressed a desire at once to annihilate and consume their victim, demanding that she metaphorically, if not literally, assume whatever posture they might devise to revitalize their waning sense of mastery. (1)

“Then I was thrown upon the ground on my back, one of the men stood on my breast, while two others took hold of my feet and stretched my limbs as far as they could, while the man standing upon my breast applied a strap to my privates until fatigued into stopping, and I was more dead than alive. Then a man, I suppose a Confederate soldier, as he had crutches, fell upon me and ravished me. During the whipping, one of the men ran his pistol into me, and said he ‘had a hell of a mind to pull the trigger,’ and swore they ought to shoot me, as my husband had been in the ‘God damned Yankee army,’ and swore they meant to kill every black-son-of-a-bitch they could find that had ever fought against them. (1)

“The klans also administered comparable punishments to women and children of both sexes. In one such episode, nightriders set upon a group of freedpeople, forcing the women to “lie down, and they jabbed them with sticks, and made them show their nakedness.” Neither did they spare the children present. Klan members instead descended upon them, “jabbed them with a stick, and went to playing with their backsides with a piece of fishing-pole.” (The klansmen were sticking a fishing-pole into the rectum of the innocent children.) Other assaults were still more severe. The son of a former Alabama slave spoke of a klansman, John Lyons, who “would cut off a woman’s breast” with little compunction. (1)

With the segregation of black into Jim Crow neighborhoods, white sexual assaults did not abate. In 1893, Fannie Barrier Williams addressing a convention of black and white women at the World Columbian Exposition on the issue of white men raping black women, was not hesitant about confronting an issue that white women were all too willing to sweep under the rug, and only very rarely discussed in public:

“Williams went to the heart of the matter. “I regret the necessity of speaking of the moral question of our women,” she began, “but, the morality of our home life has been commented on so disparagingly and meanly that we are placed in the unfortunate position of being defenders of our name.” Echoing the sentiments of (Ida B.) Wells, Williams went on to tell the group that the onus of sexual immorality did not rest on black women but on the white men who continued to harass them. While many white women in the audience were fantasizing about black rapists, she implied, black women were actually suffering at the hands of white ones. If white women were so concerned about morality, then they ought to take measures to help protect black women.

” ‘I do not want to disturb the serenity of this conference by suggesting why this protection is needed and the kind of man against whom it is needed,” Williams threatened. By implying that white men were the real culprits, Williams attacked not only the myth of black promiscuity, but the notion that women themselves were wholly responsible for their own victimization.

“Even for black women in Williams’s position the issue wasn’t an abstract one. Sexual exploitation was so rampant that it compelled thousands of black women to leave the South, or to urge their daughters to do so. Speaking before the exposition, Williams already knew what she would write some years later: “It is a significant and shameful fact that I am constantly in receipt of letters from the still unprotected black women in the South, begging me to find employment for their daughters…to save them from going into the homes of the South as servants as there is nothing to save them from dishonor and degredation.” (2)

Black women, like black men, could expect no justice in a court of law, nor could they look to authorties for protection. For example, when Patience Thompson took her case against Thomas Goss, a white man, to court for beating her after she refused to sell him soap, the court forced her to pay court costs and told her to “make up” with him. In Richmond, Virginia, the “most likely-looking negro women” were regularly rounded up, “thrown into cells, robbed and ravished at the will of the guard.” The people in the vicinity of the jail testified “to hearing women scream frightfully almost every night.” And in July of 1866, in Clinch County, Georgia, a black woman was arrested and given sixty-five lashes for addressing a white woman with abusive language. A month later Viney Scarlett, another black woman, was similarly arrested, tried, fined sixteen dollars, and given sixty lashes for thr same “offense”. (3)

On the issue of black men raping white women, it was the other way around with white women pursuing black men. In an editorial retort to a Rebecca Felton’s publishing of black men as rapists, Alex L. Manley, black editor of the “Daily Record” published on August 18,1898 an editorial that took on the rape myth point-blank, noting that what whites were quick to call “rape” was often simply an exposed liason:

“Our experiences among poor white people in the country teach us that the women of that race are not any more particular in the matter of clandestine meetings with colored men, than are the white men with colored women…Meetings of this kind go on for some time until the white women’s infatuation or the man’s boldness brings attention to them and the man is lynched for rape. Every Negro lynched is called a “big, burly black brute” when in fact many of these…had white men for their fathers and were not only not “black and burly” but were sufficiently attractive for white girls to fall in love with them…Mrs. Felton must begin at the fountainhead, if she wishes to purify the stream.” (4)

Manly then went on to address the white men of North Carolina directly:

“You set yourselves down as a lot of carping hypocrites; in fact, you cry aloud for the virtue of your women, while you seek to destroy the morality of ours. Don’t think ever that your women will remain pure while you are debauching ours. You sow the seed—the harvest will come in good time.” (4)

White men’s rape of black women continued on into the next century. Anger Winson Gates Hudson was born in Harmony, Mississippi, on November 17, 1916. She tells of the rape and mistreatment of black women by white men:

“Grandma Ange also told me a lot about being a black girl growing up. I heard her once say how proud she was to be able to marry a dark-skinned man—that she was “sick and tired of white folks.” See, three of her children were born before her marriage to Pappy George Turner and two of them were by white men. The oldest son, Whitfield Gates, and my father, John Wesley Gates, were by two white men. The two white men were brothers from the Moore family….

“Now, those two white Moore brothers didn’t have much to do with their black children, but their sister, Luna Moore, did. That would have been my daddy’s auntie—a white woman who took a liking to Grandma Ange.

“Sometimes, white wives would kind of try halfway and have a little something to do with these children their white husbands had with black women, but the white men would have nothing to do with them. (5)

She goes on to tell of the always ever present threat of rape that hung over the lives of black women and black girls:

“Southern whites saw to it that blacks had no alternative to the brutal reality of sharecropping. Their control extended to every area of life; white rape of black women was endemic, like heat and humidity, and victims had no recourse to the justice system.” (4)

Winson Hudson, in the 1920s, recalls:

“Back then, white boys would rape you and then come and destroy the family if you said anything about it. You would just have to accept it. They were liable to come in and run the whole family off. I couldn’t walk the roads at anytime alone for fear I might meet a white man or boy. I couldn’t walk the street without some white man winking his eye or making some sort of sound. This made me so angry because I had five brothers, and I heard my father almost daily warning them against even walking near a white girl or looking at them or going near a house unless they knew that white men were there too.

“Because, you know, if a girl went through a trail or to the spring–there wasn’t no roads like now—just a little wagon road, and if you were by yourself and met a white man, you just were almost sure to be raped.” (5)

She also spoke of white men who murdered their own mixed-blood children:

“One man they hung not too far from here and burnt him too. Said he was riding a too fine saddle horse. His daddy was a white man, and his daddy was in the mob. This was common around here; it never will be told just how many young boys disappeared too. Just kill ’em and throw ’em in the pond and laugh about it.” (5)

By now the sexual abuse and rape of black women was considered normal in the eyes of white society. Black women were considered as inherently aggressive and sexually unchaste. The belief had become embedded in white society that how could a white man be guilty of raping a race of women whom they considered as part of their birthright as white men to have easy access to? Over seventy years after the abolition of slavery, the white anti-lynching activist Jessie Daniel Ames would remark on the continuing influence exerted by the mythology of black female lasciviousness:

“White men have said over and over…that not only was there no such thing as a chaste Negro woman—but that a Negro woman could not be assaulted, that it was never against her will.” (6)

During Jim Crow segregation, black women continued to be victims of rape and sexual coercion:

“Subsequently, however, when Jim Crow pigmentocracy reigned supreme, blacks—and especially black women—continued to be the object of sexual aggressions stemming from the practice and ideology of white supremacy. Black domestic servants working in homes and hotels were perhaps the most vulnerable of all. Isolated from witnesses, stereotyped as morally lax, and deprived of powerful male protectors, black domestics who were raped or otherwise assaulted by white men stood little chance of receiving redress from police, prosecutors, juries, or judges. In 1912, a black nurse reported an experience that was all too typical. Dismissed after refusing to permit a white employer to kiss her, she would later recall:

“I didn’t know then what has been a burden to my mind and heart ever since; that a colored woman’s virtue in [the South] has no protection. When my husband went to the man who had insulted me, the man…had him arrested! I…testified on oath to the insult offered me. The white man, of course, denied the charge. The old judge looked up and said: “This court will never take the word of a nigger against the word of a white man.” (6)

Laws on the books throughout the South allowed white men to rape black women with impunity. The rape of a black woman carried with it none of the weight of the rape of a white woman:

“In some southern locales, white lawmakers stymied efforts to enact statutory-rape provisions that would have raised the age of consent, claiming that they would empower Negro girls to threaten white men. “We see at once,” Kentucky legislator A. C. Tomkins warned, “what a terrible weapon for evil the elevating of the age of consent would be when placed in the hands of lecherous, sensual negro women!” Moreover, some whites, still clinging to the ways of slavery, perceived black women as being essentially unprotected by law. Thus in 1913 Governor Cole Blease of South Carolina could pardon a white man convicted of raping a black woman because he refused to believe, he said, that the defendant would risk imprisonment for “what he could usually get from prices ranging from 25 cents to one dollar.” In pardoning another rapist, Blease candidly averred that he had “very serious doubt as to whether the crime of rape can be committed upon a negro.”

“Disabled from calling upon law-enforcement officials with confidence, blacks had to resort to other means of protection and redress. One of these was emigration. According to Professor Darlene Clark Hine, many black women fled the South “to escape both from sexual exploitation…and from the rape and threat of rape by white men as well as black males.” White men in Indianola, Mississippi, so menaced the black women clerical workers at an insurance company that that firm moved its offices out of state.

“In many instance, the only form of redress available to blacks was publicity—that is, the revelation of the realities of sexual criminality denied by white supremacists. The outstanding practitoner of this mode of resistance was Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a fearless journalists who exposed the failure of state officials to punish seriously those who raped black women. In one case she publicized, a white man from Nashville, Tennessee, was convicted of raping a black girl, went to jail for only six months, and afterward became a detective in that city. Such leniency would, of course, have been unthinkable had the perpetrator been black and the victim white.” (6)

As the decades went by, rapes of black women did not end. During Jim Crow segregation, black women were still being treated as less than animals. And the rapes of little black girls were not uncommon. Stine George in 1930 Florida, tells of the rape of her little sister:

“I shall never forget this, and this is something nobody ever knew because we don’t tell it. I wouldn’t tell it now because it’s so painful, it will be painful even to tell it, but with what you are doing, I’ll tell it. Some Sunday mornings we would get a mule and five or six of us would get the wagon…and go about six miles away to see my Uncle Chilton. Like I said, my sister was about nine or ten. Of course, I was driving, and she was sitting in the wagon. So we went by this house where these white guys were out there playing ball. I guess it was eight guys probably about 18, 19 or 20 years old something like that.

“One of those guys ran and jumped on the wagon. He said, “I’m going to ride with you, I’m going to ride.” We were going by this house…and he got on the back of the wagon, and he was riding with us. When we got to the house, he took the mule from me and stopped the mule at the house, took the wagon from me and tied the mule to a tree in the yard. Then he made my sister get out and go in the house with him.

“He raped my sister.

“Like I said, she was about nine at that time.” (7)

Stine George and her little brother who was with them ran away and hid in the woods. Afterwards, they saw their sister driving the wagon by the wooded area they had hid in. She tells the rest of the incident that occurred:

“So about the time we got halfway back to Gum Branch, almost back to where we could see the house, we heard the wagon going back down that road, running. See, what he had done, after he raped my sister, he told her to get into the wagon and go home. So she was driving the wagon and she went on home. She went by this house where my dad was, and all of them got out…They were alarmed. So finally they (the parents) had her…They finally called the sheriff, and of course, he didn’t do nothing. He did arrest the guy. We finally came out of the woods, and then we went back down to the house, and we didn’t have anymore trouble out of them, but they never didn’t, never do nothing to that guy for what he did.” (7)

Cora Elizabeth Randle Fleming tells a painful story about her family’s interracial heritage. Fleming’s grandmother was raped by a white man in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, in 1905. Since for a white man to rape a black woman was not considered a crime in Jim Crow courts, Fleming’s grandmother’s rapist suffered no consequences:

“They told us my grandmother was raped. Well, in those days you didn’t “rape”. You just took what you wanted from the women. They always told us that she was cold. It was so cold ice shoots came up from the ground. He raped her in those woods. . . .One child was born to that woman. Her name was Eliza, I believe. [She was a] very pretty woman, they say. Her hair was so long she could sit on her hair, braid it up. She was a very nice person. She gave birth to, I believe, 11 children. That made all of us come in from that rape.

“When I was a child growing up, one old white man lived down the road from us, way down the road. I thought he was the one that did it. He’d pass by and I’d throw bricks at him and hide behind the tree. I thought he was the one that did it. But it wasn’t him. It was somebody else had did it.” (7)

The rapes and sexual abuse of black women and girls continued on into the 1950s and 1960s. Black mothers and fathers knew of what would happen if they let their daughters go to work in the homes of white men. Because of the rampant sexual abuse against black women by white men who hired black women as domestics, many black parents forbade their daughters to work as maids or cooks since this put them into too close a proximity of white men who would rape them:

“I never had one of my daughter’s working in a white man’s kitchen,” Mrs. Tubbs continues. “None of my kids. Never. Because I’ve known a white man to take advantage of the colored woman so much, and every time they take advantage of them they dump it over in the Negro race. I know’d if I keep ’em at home they couldn’t get to them so that’s what I did, I kept mine at home, all the time. If they wanted to go to the fields and pick some cotton they could do that, if they wanted to hoe some, they could do that, but not work in that kitchen, where you come in tangle with that white man, while his wife is out.

“See all the mulattos and you know what happened, because they didn’t come from the Negro man with the white woman, it had to come from the white man with a Negro woman. They put it in the trash can because they put it back in the black race, and there’s blue eyes and everything, you’ll meet ’em, they’re Negroes, but they’re white still.

“A Negro always is in need for something, and that’s where the white man comes in, and gets his thing, see. And plenty of ’em go out, y’know, with ’em, and I’ve know ’em to just leave their wives, and go off with a Negro woman as far as they’re concerned. But usually it’s the moonlight stuff.

“And the white man always handles it so that he looks better than the Negro. He’s got the white woman scared to death of the Negro. And every white woman that howls ‘Rape,’ the Negro wasn’t raping her. Maybe he didn’t do the things he wanted to do because he was afraid. And then just happened to look at a white woman, but it wasn’t that he tried to rape her.

“If a white girl would come up with a Negro baby, he’s not going to be born, they’re gonna kill that woman ‘fore she has that baby, or get rid of her and that baby both. But the white man he can do it. Sure. You can see it. Some white men have recognized their children, they give ’em a part of their living, but they give it to their Negro children as something special they did for them, not like their own white children, there’s a mighty few of ’em do that because they don’t wanna.”

“While we are talking, a neighbor, Mrs. Annie Baker, comes in. She voices the same sentiments:

“I’d never allow one of my daughters to work in a white man’s kitchen. You can see, ‘mongst us, the results, almost white Negroes. Now it’s been all this time, our race is ruint! And didn’t no Negro man ruin it!” (8)

Grace Halsell, a white woman who dyed her skin black to live life as a black woman in the South, tells of what happened to her as a “black” woman working in the home of a white employer who tried to rape her:

“He leaves the room after a time. Soon from his mother’s suite comes a thunderous clap (the blind woman’s fish bowl has fallen from its stand is my first reaction) and simultaneously he shouts, “Come quick!”

“Hurrying upstairs, I walk swiftly into the bedroom. Instantly the door slams behind me and as I turn around I find myself encircled in Wheeler’s arms. I am momentarily overwhelmed. He presses his mouth roughly against mine and forces his body against me, muttering hoarsely about his desperate need for “black pussy.” He has already unzipped his trousers, indicating he intends few if any preliminaries. His muscles strain against me and he uses his arms like a vise to keep me from breaking away and at the same time force me onto the bed.

“Only take five minutes, only take five minutes,” he mumbles, partly pleading, partly threatening. “Now quieten down! Just gotta get me some black pussy!” (8)

She eventually breaks free of him, and he looks at her filled with rage that he cannot now rape her:

“You black bitch!” he cries, shaking with anger. More menacingly he adds, his voice lowered to a whisper: “I ought to kill you, you black bitch!”

“Go ahead, you coward!” I dare him. “You wouldn’t have the nerve!”

She runs out of the house and down the block where she sees a black family driving by, flags them down and escapes with them. Later on that evening she contemplates the ordeal she endured that morning:

“And why, my thoughts race on, could he have been so certain five minutes of lust for forbidden fruit would be his for the taking? Not for the asking, but only for the taking? In what depths of contempt he must hold all black women.

“I, as a white woman, have never seen eyes so full of lust and greed as I have as a black woman looking into the faces of white men who want to possess me. At cafe cash stands and bus-ticket counters, white men have winked at me, not flirtatiously (as might have happened, had I been white) but in a blatantly open, “come on” way, hinting at a common complicity in violating society’s color taboos.

“Always, as a black woman among white men, I have felt they considered me as in-season game, easily bagged, no licence needed.

“I begin to see the role of the black woman in Wheeler’s home objectively. She is me, and she is not me, because I could escape. And suppose Wheeler had won his claim. As he’d insisted, ‘only take five minutes . . .only five minutes,” but what might those five minutes have meant to an overburdened mother?

“Suppose he had made the black woman pregnant. The child would be her child, not his! For his five minutes of sensuality she would pay for the rest of her life. The child, no matter how “fair” its skin, would be classified as a nigger. The mother would be struggling for food and to pay the rent, sacrificing to give the child even a second-rate education. And Wheeler? He’d be at the bank appraising loans, in the church passing the collection plate, in the White Citizen’s Council making reports on the crime and violence, and blaming it on the uppity niggers.

“The words of Mrs .Annie Baker echo in my ear: “Our race has been ruin’t, and ain’t no black man that ruin’t it.” The white man causally rapes the black women, taking them as they would their smokes and bourbon—out of their own greed, their own lusting after the flesh they tell their own women is a dirty, filthy color. And for this reason one sees very few really pure black people left in the South. If the Negro husband complains when the white man rapes his wife, he is, in the judgement of many Southern whites, getting “uppity” and he risks violence and even death. So the Negro man has never been able to raise his voice.

‘If I had been a black married woman, could I have told my Negro husband: “Wheeler tried to rape me?” Then what? What could one black man have done against the entire System?

“Now I reflect how I had gone with trembling heart to the ghetto, Harlem, fearful that a big black bogeyman might tear down the paper-thin door separating my “white”body from his lustful desires. (But) it had been a white, not a black, devil whose passions has overwhelmed him. His uncontrollable desire for blackness (strange, mysterious, evil—therefore, good), simply underscores America’s hypocrisy. Sex is what’s important, it’s the root of all our racial frustrations (and a few more besides!), and the basis for over 400 years of lies [my emphasis].

“The white man created the taboos about blackness and then fell prey to them, desiring the flesh not in spite of but because it is black.

“Looking back at the centuries-old bedroom scene, seeing Mr. Wheeler with his agonized, bitter hared of me, and of himself, I realize how sad it is that you and I so often express our real selves not by joy or blissful rapture, but by the kick in the guts we give one another.

“It is man’s inhumanity to man (and woman), always and everywhere.” (8)

Black women were raped before they were lynched, as the following newspaper accounts reveal:

“Oklahoma, 1911. At Okemah, Oklahoma, Laura Nelson, a colored woman accused of murdering a deputy sheriff who had discovered stolen goods in her house, was lynched today with her son, a boy about fifteen. The woman and her son were taken from the jail, dragged about six miles to the Canadian River, and hanged from a bridge. The woman was raped by members of the mob before she was hanged.

The Crisis, July, 1911.” (9)

“CHICAGO DEFENDER

December 18, 1915

RAPE, LYNCH NEGRO MOTHER

Columbus, Miss., Dec. 17—Thursday a week ago Cordella Stevens was found early in the morning hanging to a limb of a tree, without any clothing, dead. She had been hung Wednesday night after a mob had visited her cabin, taken her from her husband and lynched her after they maltreated her. The body was found about fifty yards north of the Mobile & Ohio R. R., and the thousands and thousands of passengers that came in and out of this city last Thursday morning were horrified at the sight. She was hung there from the night before by a bloodthirsty mob who had gone to her home, snatched her from slumber, and dragged her through the streets without any resistance. They carried her to a far-off spot, did their dirt and then strung her up. The mob took the woman about 10 o’clock at night. After that no one knows exactly what happened. The condition of the body showed plainly that she had been mistreated. The body was still hanging in plain view of the morbid crowd that came to gaze at it till Friday morning, when it was cut down and the inquest held.

“The jury returned a verdict that she came to death at the hands of persons unknown.” (10)

Many black women were raped by white men after the abolition of slavery, all the way up to the early 1970s. And during Reconstruction and Jim Crow segregation, many black women who were raped, did not come forward to inform the authorities. And why should they? What white man in the law was going to believe them? Who could she complain to when the white sheriff was probably a relative or friend of the rapist? Imagine what hells it must have been like for black women for the next one hundred years after the end of slavery, to be raped, knowing that there was nothing that they or the male members of their family could do about it. The white community was against them, the white courts were against them, the white law was against them.

The Lady idealization of Southern white womanhood propped up both slavery and patriarchy. According to this symbolization, the plantation mistress was, from patriarchal perspectives, an ultrafeminine creature: delicate, sexually pure, and devoted above all to her family. Dependent and deferential to men, the Lady was, in her image, rewarded by being protected, worshiped, pedestaled, leisured, and advantaged.

“In reality the plantation mistress more often, was responsible for the management of slaves and assigned a host of onerous responsibilities. These included the production of the numerous offspring which were essential to the status and perpetuation of the patriarchy. The master’s children also had to be, and be known to be, racially pure; that is, of all-white ancestry, in a society which based slavery upon black ancestry. Thus, that the plantation mistress conform to the Lady ideal was essential to white male supremacy and to the maintenance of slavery. In other words, slavery exaggerated the pattern of subjugation that patriarchy had established.” (11)

The white Southern sexual dichotomy of the madonna-virgin (white woman)/whore (black woman) creation of the white man to justify his rape and degradation of black women and girls originated during the enslavement of black women, and continued all the way through segregation. While white Southern culture was pervaded by a double standard which prescribed female purity and yet ignored the white man’s sexual exploitation of black women, the plantation mistress blamed the slave woman, not the master, for rape-mixing, just as the white woman during segregation blamed the black woman for the sexual abominations done to the black woman by the white woman’s husband, brother, son, uncle and father. But as has been illuminated, white society’s image of black womanhood preshaped this response by labeling enslaved women as unrestrained, lascivious creatures avidly seeking sex with their masters or anyone else.

“Thus, the master could rationalize his violation of black female sexual purity as no violation at all. The plantation mistress dared not challenge the sexual double standard. If she failed to act in accordance with the prescribed Lady role, she risked incurring the same stigmatization that was attached to black women in a culture that conceptually divided all women into “ladies (always white and chaste) and whores (always comprising all black women).” (11)

Thus, with these obverse images concretized in the popular mind, the chaste belle (white woman) and the lustful female slave (black woman) evolved into rigid stereotypes. The virgin-madonna/whore dichotomy which was imposed upon white and black southern women deeply affected their images of themselves and of each other. The women of each race were thereby rendered a “fractured self,” denied a full and diverse identity by the culture of a racist, sexist patriarchy, and encouraged always to reject their racially designated female other. (11) Therefore, just as black women were forced to be strong, and their femininity and womanhood was subjugated and defiled by white men, white southern women often were compelled to appear weak, and ineffectual and not allowed to grow into their own strength.

The black woman was to be strong, tough, and unfeminine, fit only to do the work that a white man or black man should do, and that a white woman should not do. Her masculinization highlighted the Lady’s (white woman) ultrafemininity. In short, the Whore (black woman) and the Lady (white woman) were two sides of the same coin. In other words, “if one was to be, the other had to be.” (11)

And the brutally inhuman attacks upon black women’s womanhood, the taking of their bodies, and denying them autonomy and control over their bodies left lasting consequences that still haunt black women today. The Old South sought to alleviate its anxieties about seeing slave women as women. Moreover, because the sexual dynamics of slavery can no longer be ignored, it also becomes increasingly clear that, as Barbara Christian has pointed out, “the racism that black people have had to suffer is almost always presented in peculiarly sexist terms. That is, the wholeness of a person is basically threatened by an assault on the definition of herself or himself, as female or male”. (11)

This constitutes a most dehumanizing assault. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese has emphasized that for human beings, gender defines “their innermost identities, their ideals for themselves, and their views of the world.” Sexual identity lies “at the core of any individual’s sense of self. And attention to the historical continuity of this assault points to the modern myths of black womanhood as truly “nothing new.” (11)

By labeling the enslaved black woman as a Jezebel, the white master’s sexual abuse was justified by presenting her as a woman who deserved what she got. The white man could also deny the challenge posed to patriarchal mythology by this woman who could do “man’s work” by labeling the slave woman as a sexual animal—not a real woman at all.

Therefore, the white man created the mythological lies of the black woman as Jezebel/Whore/Slut not fit for human compassion, not allowed the adoration, love and protection of ALL men; on the other hand, the white man created the myth/lie of the always chaste white woman, no matter what her station in life, as always a lady, always chaste, always pious, always to have the protection and love of ALL men.

White society has historically dichotomized the conceptualization of black and white womanhood, which assigned to white women the idealized attributes of “true womanhood,” and cast black women as “fallen womanhood”. “Barbara Welter has pointed out that during the 19TH Century the Victorian cult of “true womanhood” prescribed not only female domesticity, but also chastity, piety, and dependency on and deference to men, together with other patriarchally prescribed “feminine virtues.” Thus, Palmer has noted, the “good” woman was by definition “pure, clean, sexually repressed and physically fragile.” In contrast, the “bad” woman was by definition the woman without male protectors, who provided for herself. The black woman was therefore de facto the bad, unwomanly woman, cast in Palmer’s words as “dirty, licentious, physically strong, and knowledgeable about…evil”. (11)

Therefore, while black women may be looked upon as symbols of female strength, workhorses (“mules of the world”) and as represnetatives of pathos, they are still not embraced as equals. And until this still-immense perceptual barrier dividing “good” and “bad” women is transcended, American women will never be able to make common cause and solidarity.

The myths and lies perpetuated by white men against black women that originated in the 19TH Century, and grew into full force during the 20TH Century, still remain as vestiges in the 21ST Century.

The beliefs that black women are always not to have their womanhood accorded any humanity in ALL men’s eyes still holds sway and is most blatantly seen in how the media reacts, or doesn’t react, when a black woman goes missing; the belief that white women are to always have their womanhood accorded humanity is most seen in how the media reacts when a white woman goes missing or is presumed harmed.

In my third and final essay I will speak of the different ways white woman are treated by the media as opposed to how black women are treated by the media, and how the “Missing White Woman Syndrome” continues to play out time and time again in the media.

SOURCES:

1. “Sexualized Racism/Gendered Violence: Outraging the Body Politic in the Reconstruction South”, by Lisa Cardyn. Michigan Law Review. Ann Arbor: Feb. 2002. Vol. 100, Iss. 4, pgs. 675-867.

2. “When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America”, by Paula Giddings, William Morrow & Company, 1984, pgs. 86-87.

3. “Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South”, by Deborah Gray White, W.W. Norton & Company, 1999, 1985, pg. 175.

4. “At the Hands of Person’s Unknown: The Lynching of Black America”, by Philip Dray, The Modern Library, 2002, pgs. 125-126.

5. “Mississippi Harmony: Memoirs of a Freedom Fighter”, by Winson Hudson and Constance Curry, Palgrave MacMillan Publishing, 2002, pgs. 19-24.

6. “Interracial Intimacies: Sex, Marriage, Identity and Adoption”, by Randall Kennedy, Pantheon Books, 2003, pgs. 177-180.

7. “Remembering Jim Crow: African-Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South”, by William H. Chafe, et. al., The New Press In Association with Lyndhurst Books of the Center for Documentary Studies of Duke University for the Behind the Veil Project, 2001, pgs. 14-15.

8. “Soul Sister”, by Grace Halsell, The World Publishing Company, 1969, pgs. 179-180; pgs. 196-203.

9. “Black Women in White America: A Documentary History”, by Gerda Lerner, Vintage Books, 1973, pgs. 161-162.

10. “100 Years of Lynchings”, by Ralph Ginzburg, Black Classic Press, 1962, 1988, pgs. 96-97.

11. “Disfigured Images: “The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women”, by Patricia Morton, Praeger Press, 1991.

RASHIYA BOND, missing since June 14, 2007

RASHIYA BOND, missing since June 14, 2007

MAHALIA XIONG , missing since July 13, 2007

MAHALIA XIONG , missing since July 13, 2007 TIFFANY JUNELLE ARCAND, missing since July 23, 2007

TIFFANY JUNELLE ARCAND, missing since July 23, 2007

KEINYA CARROLL

KEINYA CARROLL

JASMINE SHANAE POWERS

JASMINE SHANAE POWERS